Welcome back, comics compatriots!

Springing forth from the September relaunch of DC Comics like Athena busting out fully-formed from Zeus' noggin, here's yet another in a series of discussions of various facets of the comics medium. This is the third part of my very complex discussion of comics continuity. In the first part, I discussed the development of Marvel Comics' shared universe and DC's development of their Multiverse. In the second, I addressed how DC's attention to combining all their universes into one "New Earth" during Crisis on Infinite Earths actually created logistical problems that grew to rival any inconsistencies with the previous "Multiverse" system. I don't think it's overstating the case to suggest Crisis gave birth to the continuity-obsessed comics culture of the present day. And that brings us to this section, where I'll explore continuity gone wild.

|

| Silly season begins at DC: Tim Truman's Hawkworld. |

On top of that, by very virtue of there being only one Earth when previously there were many, all kinds of bits of history were reshuffled. Earth-2's heroes, the Justice Society of America, were now part of the history of this new Earth, but neither Superman nor Batman were their contemporaries. (Wonder Woman? See above.) And most certainly, Batman and Catwoman never married and never had a daughter, Helena Wayne, that became the Huntress. Although there would be a Huntress, her origin was dramatically rewritten. Power Girl? Now, there was a question that wouldn't definitively be resolved until Infinite Crisis in 2005.

|

| Retconning 101: The revised origin of the Swamp Thing by Alan Moore. |

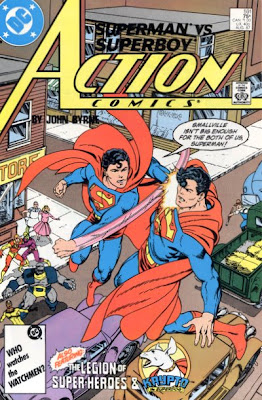

With all that DC had done in the previous fifty years, the current generation of DC's writers took it upon themselves to stitch together a continuity that was utterly fractured by the company's own hand. And the more they drew attention to the problems they created, the worse in turn those problems became. I mentioned the relationship between Superboy and the Legion of Super-Heroes in my last post. This relationship became an easy target because, well, in post-Crisis continuity, Clark Kent never became Superboy!

|

| "If there was never a Superboy, who the hell is fighting Superman?" |

Eventually, DC's continuity problems continued to grow, which led to ever more drastic measures to "fix" them. The first major, whole-house attempt was Dan Jurgens' Zero Hour: A Crisis in Time, which endeavored to fix not only Crisis but also an earlier summer crossover, Armageddon 2001, whose ending had been mishandled after fans figured out the ending months ahead of release. A time-traveling villain named Extant acted as servant for hero-gone-bad Hal Jordan, Earth's second Green Lantern, who took ever more drastic measures to bring back his hometown Coast City, which had been decimated in the "Reign of the Supermen" storyline the previous year. The series, which started at issue #4 and "counted down" toward the finale in the aptly-numbered #0, ended in a drastic re-ordering of time that was supposed to magically fix everything that came before. They even included a fold-out timeline that included events from the distant past to the far future to prove their point that everything was nearly addressed!

|

| Everything ends, and begins again. Zero Hour: A Crisis in Time #1. |

At the same time as DC dealt with their second big event centered around a "Crisis," Marvel initiated perhaps the most notorious example of using continuity as a weapon. To attempt to follow DC's lead with such events as "The Death of Superman" and "Knightfall," they concocted (there's that word again!) a storyline in which a clone of Spider-Man, who'd appeared in a series of stories in the seventies, had never died. The character, who renamed himself Ben Reilly (itself a continuity nugget, combining Spidey's uncle's first name with his aunt's maiden name), went on the road for many years but came back when he heard of Aunt May's sudden illness. His return between 1994-1996 also prompted the return of the villain that created him, the nefarious Jackal, who brought with him a host of half-baked clones including one of Gwen Stacy, Spidey's lost love. All along the way, the writers constantly refuted previous stories about the clones, bridging the gaps outside the Spider-Man group of titles.

|

| Silly season begins at Marvel: The Spider-Clone returns. |

Worse, once the "Clone Saga" was complete, writer Roger Stern returned to Spider-Man to rewrite years of continuity since he left the book, with the express aim of providing the "real" identity of the Hobgoblin. He'd already been unmasked years before as Daily Bugle reporter Ned Leeds, but that didn't stop Stern from reopening a dead case and providing his own answer to the puzzle as he originally intended. The three-issue series, Spider-Man: Hobgoblin Lives, contained references to back issues on the back covers, a sure-fire sign that continuity had been taken too far. And, of course, Stern revealed the Hobgoblin to be one of his own creations who hadn't been seen for over a decade. And an evil twin! Le sigh.

|

| The book that led to the revival of the Multive--um, Hypertime: Kingdom Come. |

Writer Kurt Busiek, who rose to prominence through his work on the revolutionary Marvels project with Alex Ross, was that unique breed of writer who endeavored in ways similar to Roy Thomas to link Marvel's past with its present. He never met a continuity reference he didn't like, and if there's one man who embodies the essence of "continuity gone wild" for better or worse, 'tis he. Marvels was filled with references both in the story itself, or in poses of characters, or really, any old thing. They may not have been intrusive to the degree they were in others' work, but there they were all the same. Busiek's intense detail toward continuity minutiae became a driving force behind two of his most well-known projects: Avengers Forever, itself a scrutinous examination of Avengers continuity through the eyes of villain Kang the Conqueror; and the DC/Marvel co-publication JLA/Avengers, itself rummaging through years of unusual continuity to tell a story that spanned the full length of both teams' histories. While demonstrating Busiek's obsessive attention to detail, both series were impenetrable to all but the most fervent fans.

|

| Continuity pr0n for Earth's Mightiest Heroes. |

Infinite Crisis in particular poked fun of the conventions of intense scrutiny of continuity when in its Secret Files & Origins special, writer Marv Wolfman revealed that since Crisis on Infinite Earths, Superboy-Prime punched at the walls of reality from the "paradise" he shared with Earth-2's Superman and Lois, with each punch causing disruptions to continuity. Those disruptions included the resurrection of Jason Todd (Robin II), the changing origins of Superman, and the various incarnations of Hawkman and the Legion of Super-Heroes. If there was an apparent continuity mistake, DC could say that Superboy-Prime made it that way. (And when he was released during Infinite Crisis, he continued the trend of messing everything up. Rimshot!)

Infinite Crisis also brought back the Multiverse in a big way, and for enthusiasts of that brand of storytelling, writer Johns "revealed" (using quotes because it was his own made-up history, not from prior precedent) that legacy characters like the Kyle Rayner Green Lantern and the Jason Rusch Firestorm were really the heroes from another, heretofore unknown Earth ("Earth-8") that was merged into the "new Earth" during the original Crisis on Infinite Earths. Yes, the writers just had to cater to the original spirit of the Crisis-that-was. But Johns kept pushing the envelope further...

|

| Did someone mention "continuity pr0n"? Geoff Johns goes overboard with the Legion. |

Not to be outdone, Marvel has done some selective continuity editing of their own, almost establishing a sort of "anti-continuity" with Spider-Man's infamous "One More Day" storyline. In it, Spider-Man made a deal with Mephisto, Marvel's representation of the devil, to save his aunt from certain death and to ensure his identity (revealed to the world in a then-recent storyline) became a secret again. Suddenly and without explanation, Spidey's marriage to Mary Jane was edited out of continuity. So ingrained into fans' minds was the idea that some additional explanation was required, that the fans were owed the details as to exactly what changes were made in history to arrive at this point. They couldn't simply accept that "they never got married" because, well, what about Mary Jane's pregnancy during the "Clone Saga"? Didn't that mean their beloved hero was having sex out of wedlock and thus was immoral and unclean? (They seemed to gloss over that part where Spidey made a deal with a bad guy, satanic or otherwise.) The "mystery" went on for nearly a hundred issues until only the points directly raised by "One More Day" were addressed, and no more, in "One Moment in Time." Of course, since then, they've moved on, content to never, ever address the finer points of Spidey's relationship with MJ again.

|

| 1st rule of Spidey continuity: You don't talk about Spidey continuity. |

Was DC in danger of collapsing under its own weight when they announced the grand reboot that spins out of the Flashpoint miniseries this month? That's a good and fair question, but it'll have to wait until my fourth and final part of this little (heh) essay.

Next: Grand Guignol

(DCnU Continuity Series: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5)

~G.

Does a story relying heavily on continuity affect the "goodness" or "badness" of a story? I'm interested in seeing reaction to your essay, as some stories such as Marvels and Kingdom Come are generally well revered. I have Marvels on my bookshelf waiting to be read; now I'm even more curious to get to it.

ReplyDeletecasual fan here, count me as one of those that loved Final Crisis - morrison has said that he tried to make an operatic/poetic myth with a very real sense of danger, portent, and unravelling doom. and creating something that tried to get away from comics taking their cues from television or movies. that guy bendis seems particularly guilty of this - all his stuff i've read comes off like it's copping the absolute worst aspects of a forensic cop show on the sci-fi channel. oh sorry i meant syfy. poetry, in particular, shouldn't explain everything to the reader, but should still get its emotional point across. final crisis did this in spades. thanks again for a great column! -peter h.

ReplyDeleteI always thought that Denny O'Neil handled things pretty well when he did the "Kryptonite Nevermore" storyline back in the early '70s. If he didn't like an aspect of continuity, he simply didn't refer to it. For instance, Krypto the superdog simply didn't fit in with the concept of the more 'realistic' (for the times) presentation of Superman which DC were aiming for, so, with one casual mention that Krypto was off exploring the universe, we never saw him again. (Until "Whatever Happened to the Man of Tommorrow?", I think.)

ReplyDeleteThat's the way to do it.

"In theory, the clone's return was meant to be a return to form for Spider-Man, who was seen as increasingly alienated from his fanbase by virtue of his marriage to Mary Jane Watson, then a successful supermodel."

ReplyDeleteI still wonder how much of a problem this really was. Certainly Joe Quesada didn't like the Spider-marriage. And I'm sure there were other creators, but I wonder how much of a problem readers had. Were the creators projecting their problems onto the readership? Were they grasping for straws trying to figure out why sales were the way they were? I mean, short of being emailed by a sufficiently large segment of the readership-emails all saying "we don't like Spider-Man being married, and want things to go back to him being single"-why is it that Marvel treated readers as if the end of the marriage was something *they* wanted (or needed)?